History

-

The First Quilt National

-

Quilt National 1979 – 2021

Purpose & Philosophy

In the late 1970s Athens, Ohio, was home to numerous talented artists. Included among this group were Nancy Crow, Françoise Barnes and Virginia Randles. These and other area artists were using fabric to create works that were pieced, layered, stitched and stuffed. These works were “quilts” by virtue of their structure, although they were intended to be viewed on a vertical plane.

The original designs and use of innovative techniques and color combinations made them unacceptable to the organizers of traditional quilt shows who were most interested in beautifully crafted bed covers with recognizable patterns. The only exhibit opportunities for these artists were in mixed media fiber shows alongside baskets and weavings. Crow and Barnes recognized the need for an appropriate showcase for what are now known as “art quilts.” They were just two of a dedicated corps of volunteers who decided to organize an exhibit devoted entirely to this relatively new breed of contemporary quilt.

Fortunately, this need coincided with the efforts of area artists and art lovers to preserve an abandoned dairy barn. Built in 1914 as part of a farm complex situated on grounds belonging to the state-owned mental health facility, the barn had served as part of the activities therapy program. Artists and others in the Athens community felt that the barn had the potential for a second life.

Quilt National was intended to demonstrate the transformations taking place in the world of quilting. Its purpose was then, and still is, to carry the definition of quilting far beyond its traditional parameters and to promote quiltmaking as what it always has been — an art form.

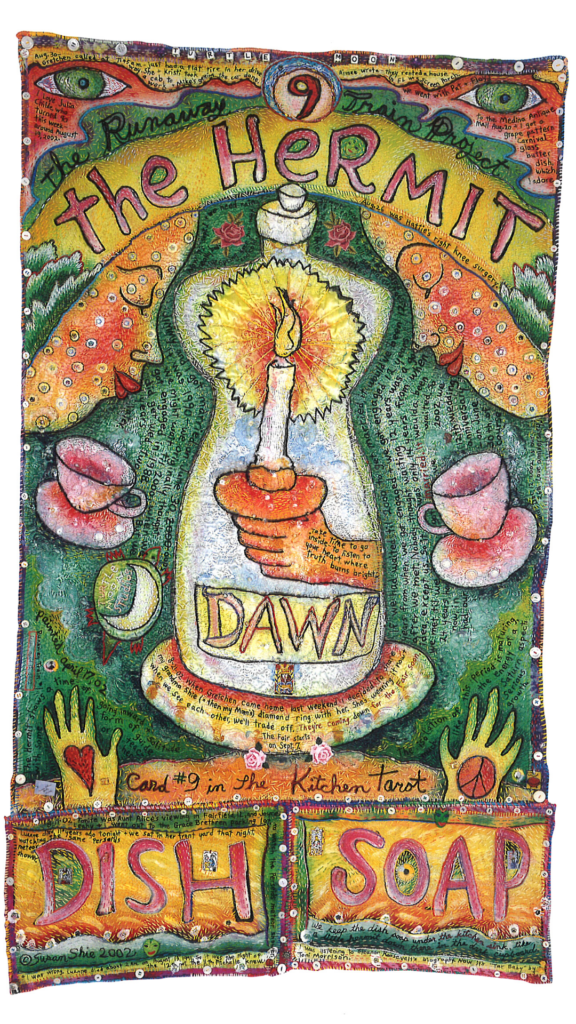

The works in a Quilt National exhibit display a reverence for the lessons taught by the makers of the heritage quilts. Many of the works hold fast to the traditional methods of piecing and patching. At the same time, however, the Quilt National artist is intrigued by the challenge of expanding the boundaries of traditional quiltmaking by utilizing the newest materials and technologies. These innovative works generate strong emotional responses in the viewer while at the same time fulfilling the creative need of the artist to make a totally individual statement.

Hilary M. Fletcher, Quilt National Director from 1982 til 2006

Hilary Morrow Fletcher, who served as Quilt National project director, died on August 11, 2006. She was a tremendous asset to the Dairy Barn and the Athens community. She walked through the doors in 1979 to view the first Quilt National. At that moment she always said that she had experienced an “epiphany”, and knew that she had found a place to devote her time.

She began her life at the Barn as a volunteer in 1980 and worked with the staff to organize Quilt National ’81. She was hired in March of 1982 as Quilt National Project Director. Through her diligence she was successful in building a foundation for an exhibit that began as one that reached across the nation into one that spanned the globe. She was a valuable resource, and was respected around the world. She traveled extensively speaking about the history and evolution of the art quilt. Her travels and lectures helped to solidify the reputation of the Dairy Barn and Quilt National both in the United States and around the world.

To us, she was more than just Quilt National Project Director. She was our mentor, our historian, our editor, our idea generator, our baker and above all, she was our friend.

In her memory, many people donated to the Hilary Morrow Fletcher Endowment fund. This fund was established in 2006 to recognize the achievements of Hilary Morrow Fletcher and to perpetuate Quilt National, a labor of love for her for the previous quarter century.

Hilary’s thoughts about Quilt National:

“This is the first Quilt National of the 21st century. As we travel the path to the future it seems like a good time to consider where we have been, where we are now, and where this path might take us in the years to come.

The history of the medium of layered and stitched fabric tells us that the 1970s saw a resurgence of interest in the beauty of one-of-a-kind handmade objects as opposed to the blandness and uniformity of mass market manufactured goods. Most of the quilt books and magazines published at the time sought to teach an ever-widening audience how to make classic pieced and/or appliquéd bedcovers.

The 1970s were also a time when there was neither understanding of nor tolerance for works that deviated from the accepted norms. This was the environment in which Nancy Crow and a handful of other artists found themselves. The purpose of the first Quilt National in 1979 was to provide an exhibit opportunity to artists whose works were unwelcome by the organizers of the existing quilt shows.

I know from first-hand experience that some visitors to the early Quilt National exhibitions never really “saw” the quilts. They were too busy commenting on the facts that the quilts were not what they expected and that they were, in the opinion of some, not what they should be. Other visitors were people like me who, once exposed to Quilt National, quickly realized that quilts could be something other than functional objects.

There were also people, many of whom are represented in this book [Quilt National ’01], who were inspired and emboldened by what they saw. They looked at works by Nancy Halpern, Michael James, and the other pioneers of the art quilt movement and recognized that this medium would enable them to make artistic statements that simply could not be made with other materials. That was where we were.

And where are we now? In the 22 years since Quilt National began, the making of both functional and non-functional quilts has become a world-wide activity. There are quilters’ organizations, publications, and exhibitions on nearly every continent. Artists from 24 countries (including the United States) submitted works for consideration by the Quilt National ‘01 jurors. Nearly one-quarter of the entries were accompanied by forms that had been downloaded from the Quilt National internet site, and 69% of those were from people who had no previous direct contact with the Dairy Barn and Quilt National.”